Reimagining Agricultural Systems Beyond Monocultures

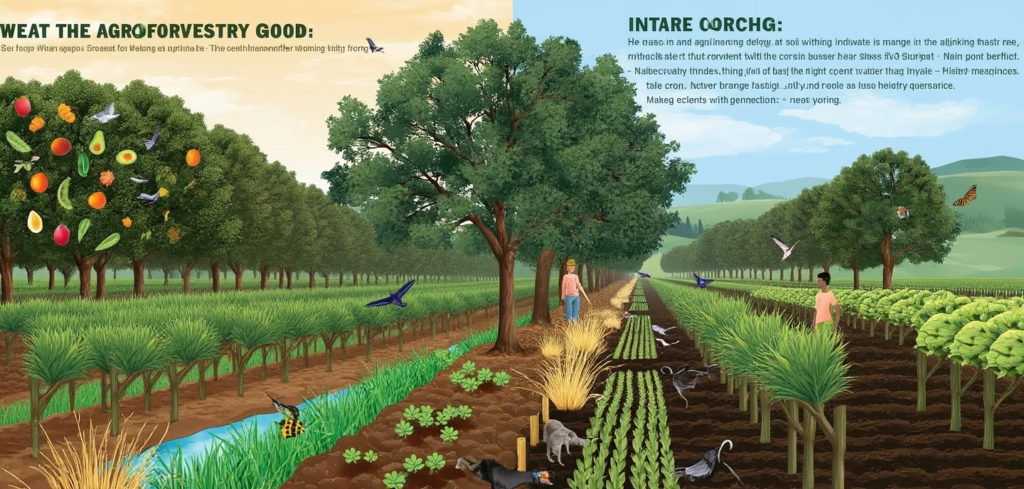

Conventional agricultural models often separate trees from crop production, creating simplified landscapes that maximize short-term yields but compromise long-term ecosystem health. Agroforestry challenges this paradigm by deliberately integrating woody perennials—trees, shrubs, palms, and bamboos—with crops and/or livestock in the same land management system. This ancient practice, refined through modern science, creates multifunctional landscapes that generate diverse products while delivering crucial ecosystem services. As agriculture faces mounting pressures from climate change, biodiversity loss, and soil degradation, agroforestry offers a sophisticated approach that enhances productivity while restoring ecological integrity to working lands.

Diverse Systems for Diverse Contexts

Agroforestry encompasses several distinct systems, each adapted to specific ecological and socioeconomic conditions:

- Alley Cropping

Rows of trees or shrubs alternate with bands of crops, creating productive alleys where annual or perennial crops benefit from modified microclimate and soil improvements. This system allows mechanized farming while diversifying production and extending the harvest calendar. - Silvopasture

The intentional combination of trees, forage plants, and livestock creates synergistic relationships where animals benefit from shade and nutritional browse, while trees receive natural fertilization and undergo pruning through controlled grazing. Well-managed silvopasture can increase total productivity per acre compared to separate forestry and grazing operations. - Windbreaks and Shelterbelts

Strategically planted tree lines protect crops, livestock, and soil from wind damage while creating wildlife corridors. Beyond their protective function, these linear forests can produce timber, fruits, nuts, and other valuable products. - Forest Farming

Cultivating specialty crops like medicinal herbs, mushrooms, and ornamentals under a forest canopy utilizes different vertical layers of the ecosystem. This approach generates income while maintaining forest cover and associated ecosystem services. - Homegardens

Complex, multi-story combinations of trees, shrubs, vines, and herbaceous plants surrounding dwellings create intensively managed systems that provide food, medicine, and materials for household use and local markets.

Ecological and Economic Benefits

Agroforestry delivers multiple advantages that address contemporary agricultural challenges:

- Enhanced Climate Resilience

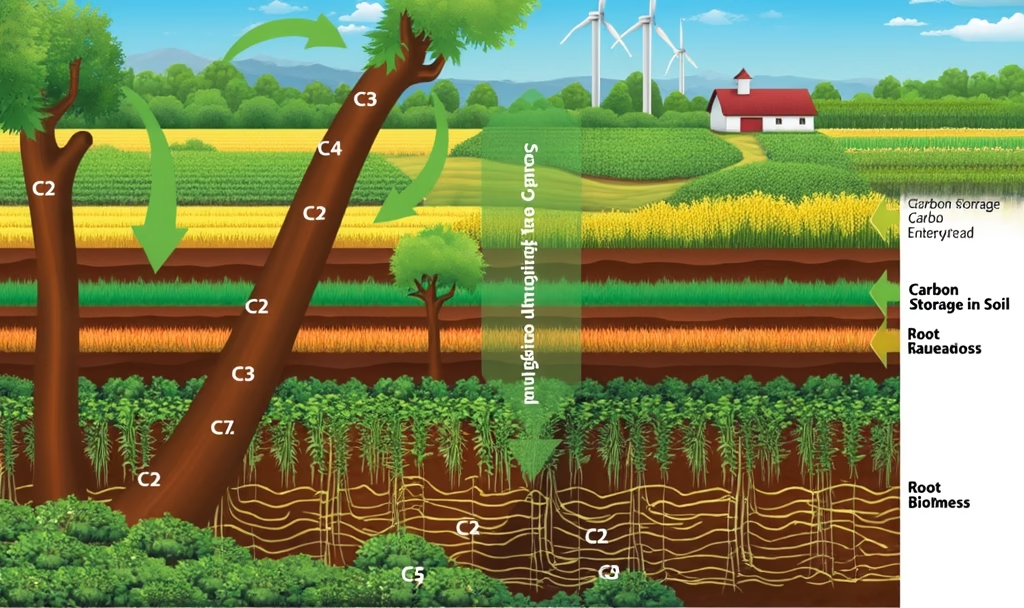

Trees moderate temperature extremes, reduce evaporation, and improve water infiltration, helping agricultural systems withstand both drought and flooding events. Deep tree roots access water unavailable to crops, maintaining productivity during dry periods. - Carbon Sequestration

Woody perennials capture and store carbon in biomass and soil, offering significant climate mitigation potential. Research indicates that agroforestry systems can sequester 2-5 times more carbon than conventional agricultural systems without trees. - Biodiversity Conservation

Complex agroforestry landscapes provide habitat for diverse species, including pollinators, beneficial insects, birds, and mammals. These systems can serve as biological corridors connecting fragmented natural habitats across agricultural regions. - Soil Health Improvement

Tree roots stabilize soil, reduce erosion, and enhance structure through organic matter additions. Many agroforestry species, particularly nitrogen-fixing trees, improve soil fertility through nutrient cycling and biological nitrogen fixation. - Income Diversification

Multiple products harvested at different times of year—timber, fruits, nuts, fodder, medicinal plants—create economic resilience by buffering against market fluctuations and crop failures. This diversity particularly benefits smallholder farmers in developing regions.

Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Despite its benefits, agroforestry adoption faces several obstacles:

- Knowledge Requirements

Managing interactions between trees and crops demands sophisticated ecological understanding. Farmer-to-farmer networks, extension services, and participatory research help build capacity and adapt systems to local conditions. - Delayed Returns on Investment

Trees take time to establish and reach productive maturity. Financial mechanisms like payments for ecosystem services, carbon credits, and specialized loan programs can bridge this gap while trees develop. - Land Tenure Security

Uncertain land rights discourage long-term investments in tree planting. Policy reforms strengthening tenure security, particularly for women and indigenous communities, create enabling conditions for agroforestry adoption. - Market Development

Some agroforestry products lack established value chains. Creating processing facilities, certification systems, and market connections helps farmers capture value from diverse outputs.

Policy and Research Frontiers

Advancing agroforestry requires supportive frameworks at multiple levels:

- Integrated Land Use Planning

Recognizing agroforestry’s multifunctional nature in agricultural policies, conservation initiatives, and climate strategies creates coherent support across sectors traditionally treated separately. - Germplasm Development

Breeding and selection programs focused on tree species suitable for agroforestry—combining rapid growth, complementary root architecture, and valuable products—expands the toolkit for system design. - Quantification of Ecosystem Services

Improved methodologies for measuring and valuing non-market benefits like water purification, pollination services, and biodiversity conservation strengthen the economic case for agroforestry adoption. - Technology Integration

Adapting precision agriculture tools, remote sensing, and modeling approaches to complex multi-species systems helps optimize management and document outcomes.

Scaling Up: From Demonstration to Transformation

As evidence of agroforestry’s benefits accumulates, attention shifts to scaling successful approaches. Demonstration farms showcase practical applications, while farmer networks facilitate knowledge exchange adapted to local contexts. Educational institutions increasingly incorporate agroforestry into agricultural curricula, preparing the next generation of land managers. Meanwhile, corporate sustainability initiatives and consumer demand for regenerative products create market pull for agroforestry systems.

By bridging the artificial divide between forestry and agriculture, agroforestry represents not just a set of practices but a fundamental reconceptualization of productive landscapes. These integrated systems demonstrate that agricultural productivity need not come at the expense of environmental health—instead, ecological processes can be harnessed to enhance resilience and sustainability while meeting human needs for food, fiber, and fuel.

References

- Jose, S. (2009). Agroforestry for ecosystem services and environmental benefits: An overview. Agroforestry Systems, 76(1), 1-10.

- Nair, P. K. R., & Garrity, D. (Eds.). (2012). Agroforestry: The future of global land use. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Waldron, A., Garrity, D., Malhi, Y., et al. (2017). Agroforestry can enhance food security while meeting other Sustainable Development Goals. Tropical Conservation Science, 10, 1940082917720667.

- Wilson, M. H., & Lovell, S. T. (2016). Agroforestry—The next step in sustainable and resilient agriculture. Sustainability, 8(6), 574.

- Zomer, R. J., Neufeldt, H., Xu, J., et al. (2016). Global tree cover and biomass carbon on agricultural land: The contribution of agroforestry to global and national carbon budgets. Scientific Reports, 6, 29987.

For those interested in designing and implementing agroforestry systems, explore Agri AI: Smart Farming Advisor that provide instant and reliable recommendations.

Leave a Reply